Predation and predator avoidance are strong selective agents. Any heritable character that allows an individual of a prey population to better evade its predators will be represented in greater numbers in later generations. Likewise, traits that allow a predator to more efficiently locate and capture its prey will lead to a greater number of offspring and an increase in the commonness of the trait within the population. Such ecological relationships between specific populations lead to adaptations that are driven by reciprocal evolutionary responses in those populations. Species have evolved numerous mechanisms to escape predation and herbivory (the consumption of plants for food). Defenses may be mechanical, chemical, physical, or behavioral.

Mechanical defenses, such as the presence of armor in animals or thorns in plants, discourage predation and herbivory by discouraging physical contact (Figure 19.14). Many animals produce or obtain chemical defenses from plants and store them to prevent predation. Many plant species produce secondary plant compounds that serve no function for the plant except that they are toxic to animals and discourage consumption. For example, the foxglove produces several compounds, including digitalis, that are extremely toxic when eaten (Figure 19.14). (Biomedical scientists have purposed the chemical produced by foxglove as a heart medication, which has saved lives for many decades.)

Many species use their body shape and coloration to avoid being detected by predators. The tropical walking stick is an insect with the coloration and body shape of a twig, which makes it very hard to see when it is stationary against a background of real twigs (Figure 19.15). In another example, the chameleon can change its color to match its surroundings (Figure 19.15).

Some species use coloration as a way of warning predators that they are distasteful or poisonous. For example, the monarch butterfly caterpillar sequesters poisons from its food (plants and milkweeds) to make itself poisonous or distasteful to potential predators. The caterpillar is bright yellow and black to advertise its toxicity. The caterpillar is also able to pass the sequestered toxins on to the adult monarch, which is also dramatically colored black and red as a warning to potential predators. Fire-bellied toads produce toxins that make them distasteful to their potential predators. They have bright red or orange coloration on their bellies, which they display to a potential predator to advertise their poisonous nature and discourage an attack. These are only two examples of warning coloration, which is a relatively common adaptation. Warning coloration only works if a predator uses eyesight to locate prey and can learn—a naïve predator must experience the negative consequences of eating one before it will avoid other similarly colored individuals (Figure 19.16).

While some predators learn to avoid eating certain potential prey because of their coloration, other species have evolved mechanisms to mimic this coloration to avoid being eaten, even though they themselves may not be unpleasant to eat or contain toxic chemicals. In some cases of mimicry, a harmless species imitates the warning coloration of a harmful species. Assuming they share the same predators, this coloration then protects the harmless ones. Many insect species mimic the coloration of wasps, which are stinging, venomous insects, thereby discouraging predation (Figure 19.17).

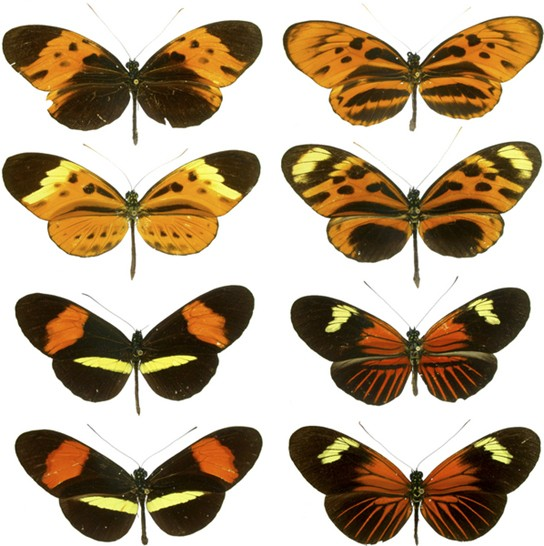

In other cases of mimicry, multiple species share the same warning coloration, but all of them actually have defenses. The commonness of the signal improves the compliance of all the potential predators. Figure 19.18 shows a variety of foul-tasting butterflies with similar coloration.

Go to this website(http://openstaxcollege.org/l/find_the_mimic2) to view stunning examples of mimicry.

- 9768 reads