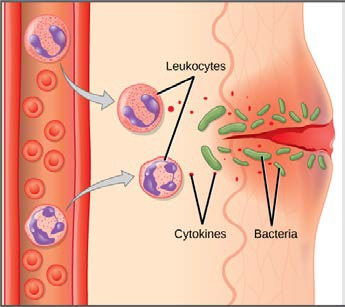

The first cytokines to be produced encourage inflammation, a localized redness, swelling, heat, and pain. Inflammation is a response to physical trauma, such as a cut or a blow, chemical irritation, and infection by pathogens (viruses, bacteria, or fungi). The chemical signals that trigger an inflammatory response enter the extracellular fluid and cause capillaries to dilate (expand) and capillary walls to become more permeable, or leaky. The serum and other compounds leaking from capillaries cause swelling of the area, which in turn causes pain. Various kinds of white blood cells are attracted to the area of inflammation. The types of white blood cells that arrive at an inflamed site depend on the nature of the injury or infecting pathogen. For example, a neutrophil is an early arriving white blood cell that engulfs and digests pathogens. Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cells of the immune system (Figure17.9). Macrophages follow neutrophils and take over the phagocytosis function and are involved in the resolution of an inflamed site, cleaning up cell debris and pathogens.

Cytokines also send feedback to cells of the nervous system to bring about the overall symptoms of feeling sick, which include lethargy, muscle pain, and nausea. Cytokines also increase the core body temperature, causing a fever. The elevated temperatures of a fever inhibit the growth of pathogens and speed up cellular repair processes. For these reasons, suppression of fevers should be limited to those that are dangerously high.

Check out this 23-second, stop-motion video (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/neutrophil) showing a neutrophil that searches and engulfs fungus spores during an elapsed time of 79 minutes.

- 10275 reads