Like proto-oncogenes, many of the negative cell-cycle regulatory proteins were discovered in cells that had become cancerous. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that code for the negative regulator proteins, the type of regulator that—when activated—can prevent the cell from undergoing uncontrolled division. The collective function of the best-understood tumor suppressor gene proteins, retinoblastoma protein (RB1), p53, and p21, is to put up a roadblock to cell-cycle progress until certain events are completed. A cell that carries a mutated form of a negative regulator might not be able to halt the cell cycle if there is a problem.

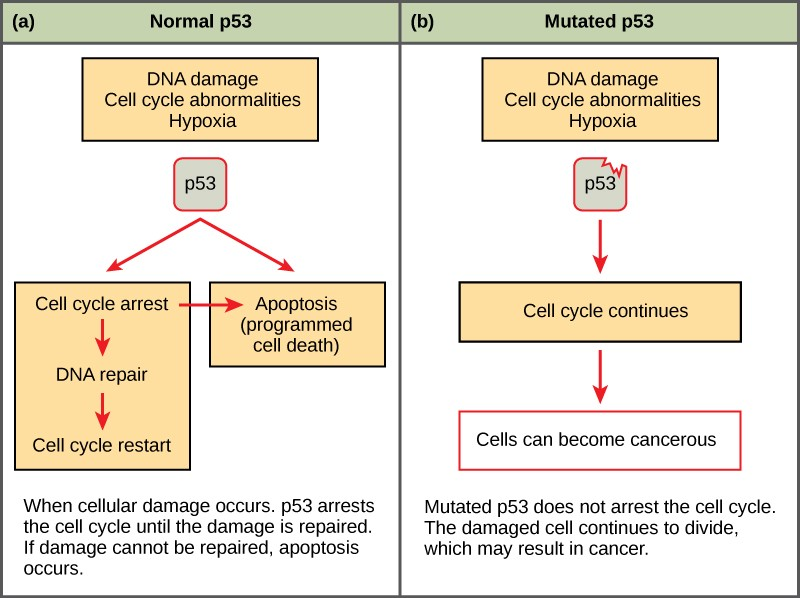

Mutated p53 genes have been identified in more than half of all human tumor cells. This discovery is not surprising in light of the multiple roles that the p53 protein plays at the G1 checkpoint. The p53 protein activates other genes whose products halt the cell cycle (allowing time for DNA repair), activates genes whose products participate in DNA repair, or activates genes that initiate cell death when DNA damage cannot be repaired. A damaged p53 gene can result in the cell behaving as if there are no mutations (Figure 6.8). This allows cells to divide, propagating the mutation in daughter cells and allowing the accumulation of new mutations. In addition, the damaged version of p53 found in cancer cells cannot trigger cell death.

Go to this website (http://openstaxcollege.org/l/cancer2) to watch an animation of how cancer results from errors in the cell cycle.

- 3582 reads